A few years ago I noticed that I was getting shorter and my lower back ached all the time. It felt like my spine had collapsed into my pelvis, which seemed impossible, because spines can’t do that, can they?

“It feels like my spine collapsed into my pelvis,” I told the orthopedic surgeon, expecting him to chuckle and tell me not to be silly; spines can’t do that.

Instead he gave me a somber look and said two words which scared the daylights out of me: “It has.”

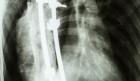

“Oh, crap!” I said. My lumbar spine had gone somewhere it shouldn’t. I watched, horrified, as he flicked a switch on the lightbox and revealed the X-ray. It was worse than I thought. My spine, which I knew was shaped like an upper-case letter S due to scoliosis, was displayed in lurid black and white, the lower part sagging between my hip bones.

“Aaargh!” I gasped.

“Don’t look at it if it bothers you,” the surgeon suggested.

I don’t know why he thought not looking would make me feel better. It was bad. My spine had gone rogue. Something had to be done.

My spine and I have never gotten along. When I was in eighth grade the gym teacher made all the girls line up in the school gym while she proceeded to tell us what was wrong with our bodies. Why anyone thought it would be a good idea to point out their physical flaws to a group of self-conscious adolescents I can’t imagine, but she did it, with gusto. A teacher doing something like that today would probably be fired and the girls would be given counseling to help them recover from the trauma, but back then nobody batted an eye. Those were harsher times.

The gym teacher talked about the three different body types. She singled me out as an example of an ectomorph, skinny as a piece of string, all arms and legs. I looked like a stick insect wearing Bonnie Bell strawberry-flavored Lip Smacker and a Toni home perm. A chubby girl named Sherri was made to stand next to me as the rest of the girls sat in the bleachers and looked on, like spectators at some kind of barbaric ritual, which is what it was when you got right down to it. Sherri was declared to be an endomorph, which meant she was fat. A girl named Barbara was selected as the lucky winner in the body type lottery: a prime example of a mesomorph, meaning she was just right: athletic, neither too skinny, nor too fat.

Barbara preened while Sherri and I stared miserably at the shiny wood floor of the basketball court, wishing a hole would appear and swallow us up.

There was more humiliation ahead. The gym teacher looked all of us over, clipboard in hand, and proceeded to judge us as if we were livestock at a county fair. When my turn came, I was given a note to take home saying that one of my shoulders was higher than the other and I had something called “cow hips,” meaning my hip bones stuck out in a way that was reminiscent of bovines. To an adolescent girl who wanted to look like Farrah Fawcett, that was depressing news. Farrah Fawcett didn’t have cow hips, that’s for sure.

What followed were years of chiropractic treatment, and an orthopedic insert in my left shoe that was intended to shore up that side of my body and make my shoulders even. When that didn’t work I was fitted for a horrid surgical corset inset with steel stays in the back and sides. The corset turned yellow with sweat stains and looked and felt like a torture device.

None of those things did a damn bit of good. My spine kept on twisting. I put up with it until it became apparent that surgery was called for. That’s how I ended up in the office of an orthopedic surgeon at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital in Manhattan, being shown an assortment of bolts and screws and metal wedges that looked like they came from the hardware store. Those bits of metal would go into my spine and help hold it up.

In an attempt to lighten the atmosphere I asked the surgeon if he got them at Home Depot.

He wasn’t amused. “No, they’re from a surgical supply company. They’re made of titanium, a very strong metal,” he said.

A thought occurred to me, “If I get shot in the spine where the metal is, will the bullet bounce off?”

He stared at me, eyebrows raised, trying to decide if I was serious. “Probably not,” he said. “But you’re not going to get shot, are you?”

I said I’d try not to.

Due to stenosis, the openings in the sides of my vertebrae where the screws were supposed to go were smaller than they should have been, meaning it would be a tight fit and I might end up with nerve damage. On the plus side, the surgeon estimated my spine would be thirty to fifty percent straighter. He said I might even have a waist! I’d always wanted a waist. Due to my spinal curvature, my torso has no indentation where a waist should be. If I had a waist I could finally wear belts! The thought was thrilling.

Then I brought something to his attention. Besides having a rogue spine I have a wonky heart. Every so often it starts beating too fast and I feel like I’m going to pass out. I asked if it going to be a problem during my surgery.

He seemed puzzled. “Wonky heart” isn’t a recognized medical diagnosis.

“It showed up on an echocardiogram one time. I think it’s called an irregular sinus rhythm,” I said, trying to be more precise.

He referred me to a cardiologist, probably deciding it was best to humor me. The cardiologist did an ECG, the results of which were normal. He probably suspected I made up my claim of having a wonky heart. It’s been my experience that doctors frequently think patients make things up, and get crazy ideas from watching medical dramas on TV. What they failed to take into account was that my wonky heart doesn’t perform on command. It likes to wait until just the right moment to start thumping wildly, like a jazz drummer pounding out a solo on the tom-tom.

In this case my heart waited until hours into my surgery, when I was opened up from the nape of my neck all the way down to my tailbone, and the surgical team was getting tired from painstakingly fitting little pieces of metal hardware into my spine while trying not to paralyze me, a real-life version of the children’s game Operation.

I imagine their reaction to my heart going wonky was one of barely suppressed panic. Being unconscious I missed all the excitement. The surgery was halted and I was hastily sewn back up again.

I was not a happy camper when I woke up. The man in the cubicle across from me in the surgical recovery unit kept shouting that he was dying. Whatever was wrong with him, he certainly had a healthy pair of lungs. His yelling added to my terrible headache. I wanted a cup of coffee but the only coffee available was decaf. For some reason the hospital was reluctant to give its patients real coffee. They were fine with rigging me up with a morphine pump and throwing in some oxycodone tablets every few hours, but real coffee was off-limits, although I suspect there was some at the nurses’ station and the doctors’ lounge.

The good news was I was alive. The bad news was that they’d had to hit the pause button, metaphorically speaking, and delay finishing the surgery until they figured out what to do about my wonky heart.

The doctors got together and decided they needed to make sure my heart was up to the task of more surgery. To find that out, they’d shoot me full of adrenaline and see what happened.

I asked the cardiologist, “What if I have a heart attack?”

I was hoping he’d assure me that wouldn’t happen, but instead he said that if I was going to have a heart attack, a hospital was the best place to have one.

That made me suspicious. “You’re not going to try and make me have a heart attack, are you?”

“No, of course not,” he said. I wasn’t convinced.

It was cold in the room where they sent me, and I was covered only with a thin cotton blanket. No matter how much adrenaline they gave me (and it was a lot, judging by the disappointed expressions on the faces of the doctors and nurses every time they shot more into the IV line and my heart failed to misbehave.) It got up to about two hundred and twenty beats per minute, as I recall, but no arrhythmia.

That irritated the cardiologist, who was clearly hoping something interesting would happen. He said he’d noticed from my paperwork that I drank a lot of coffee and snapped at me, saying I should cut down. Then he irritably summoned an orderly to roll me back to my room, where I got my husband to bring me a cup of coffee from the Starbucks down the street, black, no sugar.

I was having a good time in the hospital. My roommate was friendly, and it was pleasant to watch TV under the influence of morphine. Unlike a lot of people, I like hospital food, and the food was good there. When Rosh Hashanah came they served the best potato pancakes and brisket I’ve ever had.

Then they decided they’d better stop dilly-dallying and go ahead and finish up my spine surgery. It went without a hitch that time. I came out taller than when I went in, and while there was some nerve damage (there’s a place on the outside of my right thigh that delivers a jolt of pain when I press it, which I do occasionally to see if it still hurts) in general it’s not too bad. All things considered, spinal surgery worked out well for me. My lumbar spine was successfully hoisted out of my pelvis, although I never did get a waist.