The wild dogs howled outside my hospital window all night. Maybe they sensed that I was bleeding to death and were hoping for human scraps at the appropriate moment. I wouldn’t have blamed the staff for disposing of my body this way; we were in western Kosovo, in a hospital without stretchers or a telephone. We couldn’t communicate so they didn’t know anything about me, except that I was gushing blood internally from a fractured femur, weaker and paler by the hour. It was only a matter of time, and the dogs were hungry.

My femur had shattered while I was hiking in the rugged Rugova Mountains of western Kosovo. That this is part of a range called the Accursèd Mountains was painfully prophetic. I was walking, not slipping or sliding, when I felt a crack and a stab in my right thigh and I couldn’t stand up anymore. My face turned white from shock.

A hiking companion helped ease me down onto a trailside tree stump, and our guide Endrit came running up the trail. It was obvious from the way my leg flopped aimlessly that I couldn’t walk down the mountain, and there were no stretchers in this part of Kosovo. None.

So Endrit had to carry me down to our mini-bus. Fortunately, he was young and strong. I don’t weigh much but a hundred pounds is still a hundred pounds. When we reached the vehicle, we faced another obstacle. A log had rolled onto the muddy trail, blocking our way. Our driver Yari found a farmer with a horse, and harnessed the latter to drag it out of the way so we could pass.

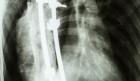

At the emergency entrance to the local hospital, the staff brought a wheelchair with no leg supports. Bending my swollen leg was out of the question, so Endrit held it up as Yari wheeled me around the hospital. From the ER we went to a dark room with an ancient-looking x-ray machine. A lab technician took only one x-ray, while Endrit and Yari waited beside me, and Endrit held my leg to keep it from bending. No lead aprons, no protective barriers.

Next, we went to “orthopedics”, where they transferred me onto one of three metal beds in a bile-green room with peeling paint. Then they left to rejoin the tour group.

I suddenly realized that I had no way of communicating with anyone. I don’t speak Albanian (the language of Kosovo) and no one seemed to speak the languages I know. So, I couldn’t ask for a painkiller, which I needed. Couldn’t ask for water, which I also needed. Couldn’t ask for the hospital’s phone number. Couldn’t ask for a doctor. Nothing.

An orthopedic surgeon arrived, Dr. Mojo, who miraculously spoke English.

He couldn’t explain to me why my bone had broken without trauma, but tried to be reassuring. “We can fix bone. No problem. Better do operation here. If you want go home to Italy, a very long cast (gesturing from chest to toes). For now we put leg in traction.”

The traction equipment consisted of three bottles of water, a roll of adhesive tape, and what looked like a sawed-off ironing board with metal legs welded on. Two nurses wrapped the tape around my leg and affixed its end to the water bottles suspended over the foot of the bed. They placed the leg on the mini ironing board and put two diapers under my right buttocks to keep those metal legs from cutting me. If I remained immobilized, all was good. But if I shifted slightly, a blur of pain descended.I tried to mimic the need for a painkiller, pointing to my leg, frowning and grimacing, but the message didn’t get through. I tried to ask for Dr. Mojo but no one understood me.

Around 6 pm a cleaning lady came by who spoke some Italian, a language I know, so I asked her for a painkiller. She told the nurses; they arrived, gave me a shot in my buttocks, and set up an IV in my right arm for a morphine drip that continued for the next three days.

However, they were far from scrupulous in their swabbing of skin with alcohol before administering shots. Sometimes they did, and sometimes they didn’t, probably because of cost. Since I was receiving four or five shots or blood tests a day in buttocks, belly, and arms, this inconsistency was troubling.

Endrit came to see me at 7 pm, bringing my electronics: phone, iPad and chargers. He was concerned that I might panic. “Don’t worry,” he urged.

“Don’t worry,” I reassured him. He left me in the fading light of my greyish-green room with rusted furniture and cracked-paint walls, and I did worry.

The insurance company called me on my cellphone, which had a little charge left. They wanted the hospital to fax my records as proof that I had really broken my femur. Since this hospital lacked a telephone, much less a fax machine, the request was futile.

A hospital staffer came in to see how I was doing. She was holding an iPhone, smiled proudly, showed me her Facebook page with pictures of family and friends, and motioned, did I want to use her phone to make a phone call? I nodded yes, remembering that in Kosovo you nod “yes” by shaking your head back and forth in a Western “no”.

Dr. Mojo appeared again that evening. He seemed pleased to tell me that my fracture could not be fixed with a cast; it required pins and screws, cutting, stitches, blood, and general anesthesia. “We can do operation here. Is free because we are public hospital. But only Thursday next. Not before.”

Granted that a fractured femur should be reset as soon as possible, how could I trust a hospital for sophisticated titanium rods, pins, and screws when it didn’t have enough money for alcohol wipes?

In majority-Muslim Kosovo, the nurses don’t wake you at 5 am; the muezzin do, followed by the ever-hungry dogs. At 7 am one of the nurses appeared to put a new dry rag under the worst wet spot made by tone of the leaking bottles, and she covered the wet blanket with a sheet.

I pulled out my iPad to check WiFi settings, and up popped one network in the area. It was private, with a strong signal and password protection. Just then hospital-staffer-with-iPhone wandered in. She saw my iPad, smiled again, held up her iPhone, a gesture that said, “We both love Apple.” My eyes lit up. I pointed to the blank space for “password”, pointed to her iPhone, made a pleading gesture with clasped hands. She understood. She typed in the password and suddenly I was connected!

Pain vanished momentarily. The grey-green walls slipped away. The rain-soaked window glowed with sunshine, and birds flew across the landscape. Finally, I could communicate with the world beyond this hospital. In my euphoria, I had forgotten to ask her to write down the password in case the connection faltered. But it never did.

Beaming, I made kissy sounds and embracing gestures to my savior, whom I dubbed “Lucky”. Then I had an inspiration. With Google translate, I asked her to summon a nurse. Then I asked the nurse for my x-ray and blood test results, and used the iPad to take pictures of both.

Google translate made it easier for me to request painkillers and water, and communicate basic concepts like insurance, airplane, cast, and travel. But not always. When my catheter tube came undone and urine leaked out, I asked for a new dry sheet. The translated response was something like, “Why you want swimming pool? No swimming this hospital.”

Two nurses came to measure me for my “travel cast”. They started to move me but backed off when I began screaming. They gave me a pain shot and said, “Docktor come do cast.”

A stocky technician showed up instead, with a buzz cut. He looked at the leg, conversed with the nurses, and said he would be back with the doctor. “It may hurt but is necessary. You understand my English? Okay you stand here till I come back.”

“No actually I can’t stand here. But I will lie here till you get back.” He laughed.

Dr. Mojo appeared with more bad news. He warned me of the risk of fat and blood embolisms, which can be fatal. The longer a fracture like mine goes untreated, the bigger the risk. I was taking enoxaparin to avoid blood clots, but the most effective way to avoid embolisms is to set the bone ASAP.

Since I did not want an operation here, said Mojo, the hospital was not going to put my leg in a cast until I was about to leave for Milan. So, no cast today.

On day three of my ordeal, I didn’t “wake up” so much as emerge from my sweaty clothes, dirty hair, and bedsores. Then more bad news. Dr. Mojo appeared and announced that I needed a blood transfusion because “You have lost much blood, 1.5 liters, from fracture. Your face pale.”

Why shouldn’t my face be pale in my situation? I thought to myself. Shock, trauma, no sun for days. “Let me think about this before I say yes,” I told him. As soon as he was gone I whipped open the iPad and read that up to half of all femoral fractures DO require transfusions because of loss of blood.

Desperate situations call for desperate measures. With my iPad, I tracked down the emails of the CEOs for my insurance company at its headquarters in France, plus Italy and the US. I pleaded my dire straits—weakening by the hour, in need of an operation and possibly a transfusion immediately, and no one was getting me out of Kosovo. I included copies of the grainy x-ray and the sketchy blood test results.

Someone in France responded within fifteen minutes. Half an hour later an Italian insurance agent emailed me back. An aereo sanitario would airlift me out the next day, Monday morning.

When Dr. Mojo came round to ask about the blood transfusion, I demurred. “No thank you. The insurance company is flying me back to Milan tomorrow.”

“You must sign form,” he said, thrusting a piece of paper at me in English. It said that I refused a transfusion despite the advice of my attending physician, and that I alone was responsible for the consequences. I signed immediately.

For the rest of the day I sent email after email to the insurance company, to the travel agency, and to my family, updating everyone and making sure everyone’s information coincided.

I began to research the reason for my unprovoked femoral break, and learned that I had suffered an AFF ( atypical femoral fracture), the result of the bisphosphonates I had been prescribed specifically to strengthen my bones. I believe that corporate cupidity had been the culprit, not a mountain curse. AFFs are more common than doctors have reported and the pharmaceutical industry—specifically the manufacturers of bisphosphonates—would have us believe.

During the ambulance ride to the airport, I looked out the window and saw sunshine over the Rugova Mountains. A good sign for my flight. “I will be just like a foreign correspondent being airlifted out of a war zone,” I mused. And I was in a war zone. You could see traces everywhere of Kosovo’s war a decade ago; roadside graves, UXO zones, destroyed buildings.

Before takeoff, the doctor zipped me into a bag that felt like a cross between a body bag (not the best analogy) and a straight jacket. My arms were free, though, so I continued to clutch my iPad across my chest. It was almost devoid of charge by then, but I wanted to honor its service by keeping it close.

During the succeeding months in hospital, rehab, wheelchair, crutches, and throughout my slow recovery (AFFs are not “normal” fractures), I attempted to track Lucky down. I tried to send her emails but they bounced: all she had was a Facebook page. I sent her a check by mail, but it came back undelivered. I found her phone number, then realized how ridiculous a “conversation” between us would be. Eventually I managed to send her an appropriate thank-you through Endrit, who led another tour group the following year and stopped at the hospital to deliver my package personally. His kindness and hers softened the curse of the Accursèd Mountains . . .but he admitted that the dogs still howl beneath the hospital’s windows. Perhaps they are waiting for someone’s broken bones. But, fortunately, not mine.