I was born into a middle-class family in the heartland of America in1952 and grew up with undiagnosed trichotillomania. For over forty years I honestly believed that I was the only person on the planet who pulled out her eyelashes. This had profoundly negative effects on my life. As an adult I have battled with chronic bouts of depression, anxiety to the point of panic attacks, suicidal thoughts and alcoholism, all of which commonly go hand-in-hand with trichotillomania. The first time I heard there was a clinical term for this bizarre condition I was well into middle age. Although this news was stunning, it didn’t change anything. I had no desire to learn more about this former blight in my life, not even out of curiosity which is unusual for me. It was enough being reminded of past insults and despair every time I look in a mirror.

A few years later, while surfing the internet, not looking for anything in particular, I stumbled across a website with stories posted by young people describing their battles with compulsive hair pulling. A few brave kids even had the nerve to display photographs of their denuded scalps for the whole world to see! Looking at the pictures made me squirm, but also struck a deep chord. Further research led me to an article that had appeared in a well-known mental health magazine, written by a young woman who grew up pulling out her eyelashes and eyebrows. I was taken aback by the striking similarities between our stories, particularly in the area of rituals, despite the fact we were from disparate generations. It was almost eerie, as if this author had stolen my story! I knew then and there that I wanted – and needed – to break my silence.

Most of my childhood memories associated with trichotillomania are dim or extinct, no doubt due to the painful and demoralizing memories associated with them. One particularly dark episode at home stands out from all the rest that I will get to shortly. The compulsion to pick surfaced when I was nine years old after I read in a book about some reason for picking out an eyelash, the purpose of which has long since been forgotten and is also irrelevant. Something that innocuous was the trigger that sealed my fate.

Pulling out my eyelashes hurt at first, but as time went by it became perversely pleasurable in a masochistic sort of way. I had to yank harder on the lashes still attached to follicles. The ones with that tiny white bulb on the end kind of “popped” when they came out. That sensation comes back to me every time I pluck off one of those twist ties in the produce section. One of the aforementioned rituals I alluded to was rolling picked lashes between my fingers to feel the textures before poking them against my lips. When a new lash started to grow in I was ecstatic, but the joy would be quickly eclipsed by the tormenting desire to tweeze it out.

I don’t know how long it was before my unenlightened, formally-educated parents first noticed that my eyelashes were thinning, but when they did they were furious. Adding fuel to those fires was the extant, long-simmering discord underscoring their marriage.

They didn’t take me to the pediatrician or consider consulting a child psychologist because they thought I was doing this on purpose, acting as if it was a personal affront to them. They also believed my appalling behavior would somehow reflect negatively on them as parents. They launched a campaign to shame me into stopping by berating and chastising me repeatedly, but their misguided approach did not work; on the contrary, as a result of their tragic misconceptions, my fragile self-esteem was ground into dust.

My mother, unbeknownst to me, spoke to my 4th grade teacher about the problem. I heard later that the young woman suggested my parents put petroleum jelly on my eyelids; the theory being greasy lashes couldn’t be grasped and pulled. I remember thinking that was a dumb idea because I didn’t understand the logic behind it. Apparently my parents weren’t impressed either; they never tried it. After the conference my teacher would sternly admonish me in class if she thought I was reaching up to pick at my eyes, “Patsy, get your hands away from your face!” As far as I know, that was the closest my parents ever came to talking with a professional. To outsiders, the family’s disgrace was a well-guarded secret.

Needless to say, our house was not a cheerful place. My mother was cold and antagonistic towards me. My brother and I fought venomously for our parents’ attention. My father had a fearsome temper. I felt like an animal caught in a trap whenever dad demanded that I close my eyes so he could see how much damage had been inflicted. Those three simple words, “Close your eyes!” always precipitated an ugly, humiliating encounter with him. The disturbing episode I briefly touched on earlier occurred at the dinner table. I still recall that night vividly half a century later. I sat cowering in my chair as my father glared at me from his end of the table and told me I looked like a monkey’s ass at the zoo – his exact words. As he raised his arm and imitated a primate picking at its armpit he sneered “Are you going to start picking out the hair under your arms next?!” My older brother and biggest rival - who was sitting across from me - burst out laughing uproariously. My mother didn’t intervene.

Regrettably, I never broke the crippling chain of co-dependency on my parents until the day they died. I always told them exactly what they wanted to hear, shielding them from the grimmest realities of my life, still afraid they’d reject me otherwise. This may sound cold, but I honestly don’t miss them. I was relieved when they passed away. They were miserable people. Any feelings of sadness or grief I have are for the unconditional love and joy my brother and I were denied in our toxic childhoods.

When I was in grade school a family with three kids moved in next door. The eldest child, a boy, took an immediate dislike to me and didn’t hide his scorn. He nick named me “Bald eyeballs.” Knowing how cruel kids can be, it stands to reason that I was a target. Eyelashes did not grow back overnight and I had to go to school. A few of the mean boys harassed me as I walked to and from school. They’d block my path and taunt me mercilessly. One even hit me in the mouth. I was so upset my mother decided she wanted to see for herself what these bullies were doing so she devised a plan. As I walked to school one morning she followed from a short distance away in the car, driving slowly like an undercover cop trailing a suspect. For some inexplicable reason I blew her cover by suddenly yelling “My mom’s here so you better leave me alone!” My mother was ready to strangle me; so much for surveillance.

Whenever I saw a commercial on television or in a magazine for cosmetics I died 1000 agonizing deaths. All the models had flawless features and large beautiful eyes with perfect, upswept lashes. Those gorgeous airbrushed faces were salt poured into an already-raw, gaping wound.

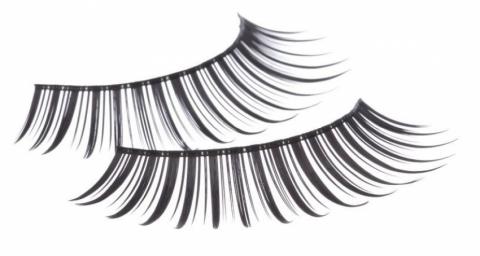

I bought my first pair of false eyelashes in high school. Once they were safely glued in place, camouflaged under a thick application of eyeliner, I felt secure enough to set foot outside; without them I looked like a gargoyle. Through trial and error I settled on one particular brand as my favorite. Not only did they look the most natural, they were also durable; the latter an important factor since I wore them every day. At $2.50 a set it was imperative to get as much mileage out of a pair as possible. Each night after carefully peeling them off, I soaked them in water long enough to loosen and remove the adhesive, reshaped them on a tissue and left them overnight to dry.

I’d be lying if I said I don’t get urges to pick at my eyelashes or other parts of my body now and then. After living with this disorder for 50 years I know myself pretty well, though. I will always feel strong urges to pick or pluck or scratch obsessively at times, but I don’t lose sleep over it and it doesn’t get the better of me either. After painting my face for so many years, today I’m hard pressed to wear any makeup outside of work.