“Hi, Mr. and Mrs. Duffy, we’ve been expecting you. I’m the head nurse at the Fetal Center, if you will follow me please,” she said signaling us to follow.

For the first time in my pregnancy, I had no wait time. Perhaps this underscored the severity of my condition. Efficiency at a doctor’s office was never a good sign. It felt as is we were in another world completely. The world where pregnancies had gone awry.

What damage had the twin-to-twin transfusion caused? Were my babies okay? Would we have to have surgery? Would there be lasting effects?

We did lots of scans with different sonographers that morning and waited. The pressure building in my back while lying on my sciatic nerve hurt like hell. Finally, after the heart sonographer had finished, the nurse came back into the room.

“The doctor will discuss the results with you now,” she said helping me out of the exam chair.

We followed her into a consultation room—four blank walls, a small window, a table and a white board. She left the room, and a few seconds later a tall doctor, maybe in his mid-fifties appeared in the doorway. He introduced himself to us.

“Hey guys, I’m Dr. Doom,” he had a gentle voice, not soft, but not loud and abrasive either. He had big brown eyes and a mustache and beard that he stroked sometimes when we spoke. He reached for our file that was on the outside of the door.

This is it. How bad can it be? Not that bad—right? Or tragically, irreversibly bad? My thoughts bounced from best case to worst case and back again. He minced no words. He glanced back at our chart.

“Looking at the results of the scans, it’s apparent that—one of the twins—Baby A is sick.” He emphasized the word, “sick,” in a way that screamed severity.

“Oh no, Baby A, that’s Katherine, our little Katie,” I cried.

“How? What specifically?” Ed jumped in.

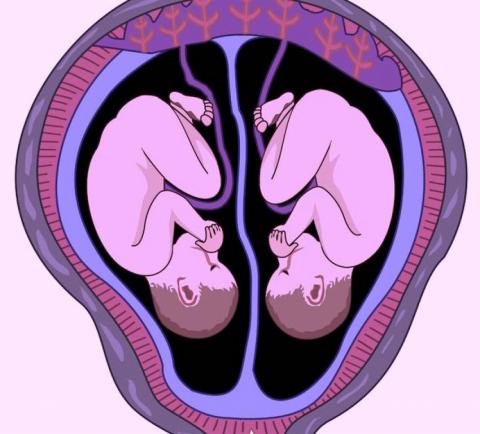

“Well you see the transfusion that has occurred here between the twins, resulted in Baby B, who we call the donor twin, experiencing low blood volume. So our focus with this baby is that she is growing at a slower rate than her sister.”

“Aww, that’s Lauren,” I said.

“And with Baby A, the recipient twin, her heart has been overloaded with blood from her sister. All this excess blood has put a strain on her heart and…” He paused for a moment.

“She’s in heart failure right now. If we don’t operate, there’s a greater than 90 percent chance that both babies will die.”

What? Die? Are you kidding me? Who said anything about dying? I couldn’t wrap my mind around it. My stomach hurt from nerves, my back ached from the scans, and I wanted to throw up I felt so nauseated. My face was turning red and I choked back tears.

My head was spinning. I only heard half the words he spoke. I did everything to try to keep it together. My sobbing would distract me from getting all the necessary information. I knew I could count on Ed, who was frantically taking notes and would remember every detail anyway, but I wanted to listen closely for myself so I could make the best decision for my girls. I couldn’t mess this up. I must be strong for my girls. This thought calmed me and infused me with a tinge of courage.

Dr. Doom went on to explain the surgery. “We will put Crystal completely under and take a laser—in utero—and cut some of the blood vessels connecting the girls to each other. This will separate the placenta so that each baby gets an equal share of it. Right now they are sharing a placenta which—as you guys know—is what caused this problem.”

Wait a sec, Jedi master, you want to laser inside me? That’s insane. The girls were created from one egg splitting, they were intended to share a placenta, won’t that harm the girls trying to create two placentas?

Of course Ididn’t speak. As he continued to describe the surgery, I kept imagining my girls, so vulnerable, being operated on before they had even entered the world. What a way to start a life. I mentally checked out for a few minutes—Ed and Dr. Doom continued to discuss the surgery. It was all so intense, I wanted to wipe my face and blow my nose. There was one lone box of tissues. I tried to reach it but it was too far. Who put only one damned box of tissues in the conference room of doom where, almost every day, a stream of bad news had been given to other parents in our situation? I could have tried to signal Ed to pass it to me, but he was in the middle of a serious discussion with Dr. Doom.

“We also need to talk about our plan if it looks like one baby simply isn’t going to make it. If one baby dies, usually the other will too, unless we intervene. So we have the option of tying off the umbilical cord of the dying baby to try and save the other baby.”

Holy shit! How had things come to this? I couldn’t take it anymore. I sprang up from my chair and as I sprinted out the door, I heard his voice trail off.

“I’m so sorry, I know this is incredibly difficult. I’ll give you and your wife a few minutes to process this information.”

I stood in front of the bathroom mirror with tears streaming down my cheeks, thinking: this is an impossible choice. How could we ever choose to save one baby over the other? And which would it be—Baby Katherine or Baby Lauren? How could we live with ourselves? How could the doctor ask this of us? How could anyone ask that of a parent?

I’m not doing this. We are not having this conversation. We’re taking it off the table.

I turned on the faucet and splashed cold water on my face and neck. I mopped off my face with a paper towel, took a deep breath, and walked back towards the room. I opened the door and Ed rushed over to me. For the moment we were alone.

“You okay?” he placed his hand on my back.

“No, not really. That’s a terrible thing he just said. How can we just give up on one of our babies?” My eyes filled up with tears. “How could we live with ourselves, Ed?”

“Yes, but how could we live with ourselves if both babies died, and we could’ve saved one?”

“Well, let’s just hope it never comes to that.”

I knew we needed to get on with the surgery and pray for the best outcome—that was about all we could do, the rest lay in the surgeon’s hands and the hands of God.

That night, I tossed and turned, checking the clock, attempting to calm myself, trying different positions, getting up and pacing and starting the process all over again. The few times I dozed off, the day’s worries in my subconscious gathered and morphed into frightening scenarios of the next day’s events.

I had so many tearful moments since our diagnosis—tears of anger and confusion. But I was finally moving past that. I truly believed that the twins and I were one entity. Whatever I felt, they felt, whether it was joy or sadness and everything in between. If I let myself surrender to darkness, depression, and negative thoughts, I feared my outcome would be darkened as well. So I no longer allowed myself tears of anger and sadness, no more worries or anxiety. Only faith. Positive thoughts and lots of prayers. It took everything in me to remember the happy moments of my life to overshadow this frightening place.

We arrived at the hospital early for our pre-op meeting with the doctor.

“Right this way Mrs. Duffy. If you’ll get undressed and remove any jewelry or make-up, then put on this gown. The doctor will be in in a few minutes,” said the pre-op nurse.

As I thought about the dire situation, I could not help but fear that my little recipient baby, Katie, could already be gone. The dread only grew when the nurse turned on the machine and Dr. Doom moved the sensor around. I felt conflicted: I wanted to know the truth, but I didn’t really. If Katie was already gone, I would be devastated. I didn’t know how I would be able to get through this surgery already knowing the outcome. Ed was right beside me, throughout the entire scan, holding my hand and reminding me to just breathe deeply. Just get through the next couple of moments.

To my relief, the doctor looked at the screen and said, “It looks like we still have both babies.” It wasn't exactly a ringing endorsement; the status quo had been preserved, but the status quo wasn't exactly optimistic. Then Dr. Doom’s slight smile conveyed that the twins’ condition might actually be looking up.

“Look here,” he said to the nurse as he pointed to the screen, “You can see that the ventricles in the recipient’s heart are showing improved diastolic flow.” The nurse smiled and nodded.

Dr. Doom continued, “It’s quite remarkable to see this level of improvement after just 24 hours of the nifedipine treatment.”

Ed grabbed my hand and squeezed it. Finally, I thought, maybe we'd turned a corner. Things were starting to improve. My calmness and positive energy had paid off. But we were by no means out of the woods yet. Hell, we hadn't even had the laser ablation surgery yet, nor did we know whether it would even be feasible. But, for the first time in what felt like forever, we had a piece of good news. My babies were both alive, and they were already starting to feel better.

A few more minutes of waiting and I was ready to be rolled down to the OR. Dr. Doom asked us whether we had decided what to do if they determined they could only save one of the babies – whether we wanted him to tie off one umbilical cord to try and save the other. Ed and I had discussed this the night before, knowing that they needed an answer before surgery. We had thought hard about what we were going to do if we were faced with this terrible situation. The twin-to-twin diagnosis was terrible. But there was something terrifying about having to even think about this question. How would we deal with a situation where neither twin would survive if “nature ran its course” while killing one might save the other? How can someone weigh the survival of one’s child against the moral opprobrium of killing one’s child? It was the worst paradox that a parent could imagine.

Ultimately, we decided that the doctors should try to save both, even if this reduced the likelihood of the healthier twin (the donor in this case) surviving. But, we said, if there was no chance of the recipient surviving, we authorized the doctors to do whatever they needed to save the healthier, donor twin. Either way, it was a nightmare, and I prayed it wouldn’t come to that. I cleared my mind of these possibilities and returned my focus to the positive news we’d heard: both girls were alive and doing better.

They rolled me into the OR and after a few minutes of additional prep, they asked if I was ready. “Yes, I said. Let’s go.” I was told to start saying the “A-B-Cs” backwards and before I got to “W” I was asleep.

An unknown amount of time later, I slowly emerged from an anesthetic induced slumber to the sound of the incessant beeping from the heart and oxygen monitors. Ed was at my side and asked me how I was doing. He told me that the surgery had gone really well – that both girls looked okay and that Dr. Doom had been able to get a good separation of the placenta, meaning that the fluid imbalance and the blood flow problems should improve.

But Ed went on, “When they inserted the needle into the umbilical sac, they nicked the inter-twin membrane. It’s not as bad as it sounds, but it’s something they’ll need to monitor. It’s just a small hole in the membrane now, but the doctors think that soon the twins will tear it down and start swimming around each other. In a few weeks, they’ll want you to go inpatient and stay at the hospital for monitoring until the babies are ready to be delivered.”

For the first time since I had learned of the diagnosis, I let thoughts about the long path ahead sink in. The ablation surgery had just been one step along the journey, the most daunting step perhaps, but, still, the first of many. I realized the doctors would need to scan every few hours to make sure there weren’t any signs of umbilical cord entanglement or compression – which could be fatal. We had weeks to go before the babies were viable—where they had even a remote chance of surviving in the outside world.

And so I prepared to continue waiting and praying and do everything I possibly could to keep my girls for another ten weeks. A long road was ahead of me. But I knew that day that I had just gotten past was the worst of it. That I had stood at the edge of an abyss and through the grace of God and the skill of an excellent cadre of doctors given my girls a fighting chance.