“What if I don’t want to?” I ask.

The head gynecologist looks strangely at me. She is a beautifully efficient woman who knows exactly what she’s doing. I couldn’t be in safer hands. My arm curls up protectively over my stomach.

“Well,” she says slowly. “The ultrasounds have revealed nothing, and given your pain is only increasing, a laparoscopy is the next logical step.”

My gut twists. Logic has nothing to do with this. Then I take a breath. I can do this. I can. I can also try to get out of this under the pretense of being reasonable. “Are there any other options? I remember you said that the Pill might help, if it was a hormonal thing...”

My feet swing nervously. I’m sitting on top of the examination bed, and my overactive imagination is supplying images of me lying down with metal sticking out of me. The gynecologist is gentle, but firm.

“Prescribing you the Pill might help your symptoms,” she agrees carefully. And then she dashes my hopes. “Or it might cover them up. On the other hand, a laparoscopy will help you actually find out what the problem is, and that way we can treat it more effectively.”

The mountain of logic builds up. I want to bury my head in my hands and hide. Somewhere, at the back of my mind, I know I’m acting unreasonably. She has explained the procedure. It’s not a big deal, like a triple-heart bypass or anything. In fact, I feel like a fraud. My mother recently underwent breast surgery for a locally advanced breast cancer. How can I complain about this?

I take a deep breath. “Can I think about it?”

Her face softens slightly. “Of course.”

I get into my car with the information leaflet about having a laparoscopy burning a hole in my bag. It is filled with supposedly helpful images showing exactly where and how the metal goes into the fleshy bits. I don’t really want to know, and I can’t think properly. There’s an odd numbness spreading through my skull as parts of me try to inventively create lurid pictures of what I imagine surgery to be like (influenced heavily by flashy medical shows on TV), while the other part tries to shut them out of my brain. I try to concentrate on the road without brooding. When I had first started feeling sharp, shooting pains inside my lower abdomen and thought to get them checked out, I had never expected it to get to surgery. Despite the fact, or maybe because my family is headed by a pharmacist and a psychologist, we’ve never really gone to doctors much, even when my sister graduated and became one and my brother started studying to reach that same goal. I was used to my complaints being treated by supplements or some over the counter thing.

And now...

I head back to work. Going to the gynecologist’s took up most of my lunch break, so I throw myself into paperwork and administration and try not to think about that damned information leaflet. I’m partially successful. But it goes downhill from there when I get home and my sister is at the table, reading a newspaper in the late afternoon sunlight.

“The gynecologist says I should have a laparoscopy,” I blurt out.

I don’t know what I’m looking for. Actually no, scratch that, I do. I’m looking for sympathy. A big mug of tea. Warm hugs. Assurance that everything will be all right and that I don’t actually have to be cut open. I am petrified of this, and I know I shouldn’t be, and fear and guilt are an unholy mix.

My sister slowly puts the paper down. She’s tired, it’s been a long day. She works with premature babies, and so she sees a lot of life and death.

“Ah,” she says. “I’m not surprised.”

“Um, what?” the disparity between what I had been expecting and what I just got is a little too much for me to handle. I sit down.

My sister shrugs. “I told you when you were first referred that it was a possibility.”

I blink. Several times. I have absolutely no recollection of this - I thought the first time I had ever heard the word ‘laparoscopy’ was today. I wonder if I wiped it from my mind or it just never happened because since the news I’ve been in an alternate reality. She sees my shock. “It’s not a big deal, you know. It’s not even real surgery, if you want to think of it that way - they just open up two tiny slits and then...”

I throw up a hand. “Whoah, whoah, that’s enough.”

My sister has attended surgeries, autopsies, and been involved enough in births that she’s pushed her slim hands up a woman’s womb to tug out the placenta. I wince every time someone throws a punch in a gritty action movie. She looks at me, and suddenly pity joins the clinical helpfulness in her eyes. “Have you even looked at the information leaflet yet?”

Uh, no.

We look at it together. She gently explains everything I don’t quite understand. It helps, but it also makes me even more afraid, solidifying my ambiguous fears about being cut around more definite ones like the risk of the surgeon accidentally damaging my bowel and then having to convert my tiny, belly-button slit surgery to a full on abdominal one. Never mind the whole bleeding to death business or the danger that comes with every use of general anesthetic.

My sister calms me with every one, or at least tries to reassure me. “There are risks with every surgery,” she says. “And you’re with one of the best gynecologists around in this area.” She grins. “Really, the only thing you need to worry about is that now you’ll never be able to become an underwear model.”

Huh. I’ve never, ever, entertained the possibility of becoming an underwear model. I’m the kind who likes to hide from their body under big baggy shirts. But now that I’m being told the option is being taken away from me, an option I never wanted, I feel an odd sense of unreasonable loss.

“But I don’t want to have surgery!” I whine. I know I’m being a child, but at that moment I need to be, because I want to be hugged and protected from this world of scars and accidental bleeding and possible death. “You know what, I think living with the pain is better than this.”

She stares at me for a moment. And then she takes a breath and says “Look. It’s a really, really common procedure. Thousands, tens of thousands of women have it, every year. You’ll be fine.”

It’s not obvious at first, but those words change something in me. Like seeds planted in fertile

ground, there’s no immediate effect. But by the time I head over to my partner’s place the next day, tossing the information leaflet at him like torn pages out of a horror novel and demanding that he try to understand my fear, some of the wind has gone out of my sails. It’s somehow oddly comforting that I’m not alone. That thousands, tens of thousands, millions of women have gritted their teeth in the past and just dealt with it, picked themselves up, and moved on. I feel like I’m in some kind of sorority, a ghostly sisterhood packed with hundreds of thousands of people that I don’t know and will never meet. But it doesn’t matter. They have shared my experience, likely, of being afraid and apprehensive of their first surgery, or even just anxious about what diagnosis such a procedure might bring. They have been strong.

The gynecologist gave me a week to get back to her about my decision. I get back to her in two days. In the face of such courage, even nameless and faceless, it would feel fraudulent to do anything else.

n the days before the procedure, my partner hugs me, and listens patiently to my rants, and offers to drive me to the surgery, wait for me, and then drive me home, even though he has evening classes that night. My older brother tells me that being under general anesthesia when he got his wisdom teeth out gave him the best few hours of sleep he ever had. Even my mother, only months out from the surgery that took her entire breast off, comforts me and tells me it will be okay.

With all that, I don’t walk into the anesthesia room feeling alone.

I am surprised when I wake up. It seems like I only just closed my eyes. I think of my brother talking about deep sleep, but it feels more as if I’ve just been so unconscious my memory and sense of time has been wiped. The word ‘groggy’ does not quite do justice to how I feel, because mixed in with it is the heady sense of relief. It’s over.

With that in mind, I remember my partner’s evening classes and try to move. There is a glass of water waiting for me on the bedside table. I stretch towards it and am instantly reminded that, no matter how small the hole was, my abdomen did just get sliced through and disagrees with such horizontal, twisting movement. I lie back on the bed and conserve my strength, getting ready for another try. It literally feels like an effort to lift a finger, like the anesthetic has turned my blood to stone. A nurse notices my aborted movement, comes over and gently tells me to rest a bit longer, that they have to wait at least an hour and a half or more before the anesthetic wears off enough for me to leave. She brings the glass of water to my hand. I ask her what time it is. She tells me, and then goes off to attend to someone else.

An hour and a half? I think. Let’s aim for an hour. And I do, continually conserving and then testing my movement, insisting on dressing myself when my clothes come, even though everything feels leaden and I suddenly wonder who the hell designed bra straps to be so hard to put on. I hobble out into a room full of stuffed couches and magazines and see my partner sitting there, waiting for me, and everything becomes a little bit better. There is a sharp, shooting pain in my abdomen that dulls to a throbbing ache whenever I try not to move... but everything is a little bit better.

We drive back earlier than suggested at my insistence. He is still horribly late for his classes, but it feels good to focus on something else, to have a goal to aim towards when my first reaction is to curl up, feel sorry for myself, and sleep forever. It’s as if I have to make up for my wildly careening fears before surgery by being extra tough afterwards.

This, however, does not extend to the use of painkillers. I down those things like sugar pills every couple of hours, desperate to stay as mobile as possible. It is one of the few concessions I allow myself - I am a little sheepish about how quickly it was all over and how small it was. I begin to realise that my fears stemmed from a conscious appreciation of getting cut. Being blissfully out of it while it all happened makes the distorted picture of massive blood and disaster in my head much tinier with distance.

I plan to go back to work much earlier than I technically need to, and spend most of it half-hobbling as I arch over my belly protectively. This comes as a big surprise to my colleagues, who had no clue I was even having problems. I laugh it off and pretend to be brave and say that at least it’s all over now. I even joke and exchange war stories with a friend who just got seven stitches in her thumb from an accident with a kitchen knife. A number which is actually greater than mine.

Less than a week later, I have healed so fast it becomes imperative to get the stitches out before they become a permanent part of me. This is where I get even luckier, with my own, talented homegrown doctor. I lie on the couch and watch as my sister delicately applies the alcohol and then snips away the stitches. It hurts a little, but because I can see and I know exactly what’s happening, that somehow makes it okay. It helps that with each thread pulled out, I feel a little bit closer to moving on and putting this behind me. I’m eager to run around and jump again, and maybe dance for the hell of it. It’s over.

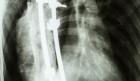

About two weeks later, the results come in, along with some interesting photos that they snapped using the laparoscope. I’m gruesomely fascinated by this intimate look at my insides, and how squishy they look. My dad takes a look and says “Ewww...” before my sister shoves him in the ribs. I smile.

They end up not finding anything, and prescribe the Pill to manage my pain. I can’t entirely escape the feeling of being cheated, a little. But more than that is the overwhelming relief that nothing is apparently structurally wrong with me - it’s more likely to do with the chemicals and other things floating around in my bloodstream. In the months before the laparoscopy was suggested, words like cysts and pap smears and endometriosis had been tossed around like confetti, so to find out there’s nothing structurally wrong is oddly comforting.

These days, I occasionally surprise myself when I look down and see my scars. They are still livid, obvious things, as tiny as they are. I rub my fingers across them, feeling the smooth rise and fall of the tissue. Such little things. It’s kind of funny that I was so scared about them before.

I’m still afraid of surgery, to some extent. I don’t think surgery itself is ever something that anyone looks forwards to. The difference is that now I know I can push through that irrational fear and see to the heart of things. I am surrounded by loving family and friends. I can, as safely as possible, put myself in the hands of a great team of doctors and nurses and medical specialists. And most comforting of all, when I rub my scars, I sometimes feel like I’m tapping into the pulse of thousands of nameless, faceless women. And they give me strength.