After it happened, my father said what people always say when there is an absolute absence of anything positive to say: “Think of this as character building.”

I am nothing if not a pragmatist and it had been a bad month. A terrible month actually. The beginning of October had been marked by my inexplicably vomiting all over the steering wheel of my car on the way to work. The same week my urine adopted a particularly concerning orangeish red hue. By the end of the week, my eyes had a yellow cast and the palms of my hands started to look very Lisa Simpson.

My father is also a pragmatist. And a physician. The bulk of my brothers and I’s medical ills have been addressed with one (or all) of the following prescriptions: exercise more, drink more water, quit watching so much reality TV and/or begin a daily Vitamin D supplement. And, in all honesty, I didn’t think this situation would be that different. I casually emailed him the morning of my law school Torts midterm and explained my situation under the considerably sarcastic subject line “Fascinating Medical Mystery.” I knew it was more serious when two hours later my father was on the phone explaining to me that he thought my liver was failing; two days later I was having my blood taken for a liver panel, one week later I was hospitalized; two weeks later I was officially withdrawing from law school for medical reasons; three weeks later I returned to work for half days and by Halloween, I felt and looked dramatically different.

For whatever reason, I did suffer severe liver failure and was extremely fortunate to catch it early. Thanks to a daily cocktail of high dose prednisone (also known as steroids- not the kind that build muscle but the kind that manage inflammation), I managed to keep my liver but shortly thereafter, I adopted something called moon face (a side effect of prednisone) and lived with the condition for the following six months.

During my adult life, I have tried to not take things for granted. I both understood and appreciated that my life had been easy, which is why I was unprepared for something so difficult. When I started the prednisone, my father said to me, “It’s a very hard drug.” And with the arrival of moon face, I suddenly knew exactly what hard meant. My face was swollen beyond recognition and it didn't look heavy so much as it looked deformed. It took on an almost perfectly circular shape (hence the term moon face); my skin was so swollen with water that it was now taut to the touch; and, my chin had all but disappeared amongst the swelling. I looked absolutely nothing like myself.

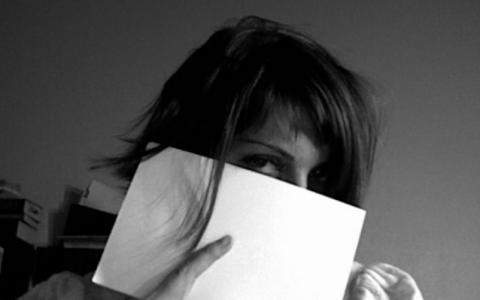

There is a black and white photo of me from this time period sitting alone in our study with a blank white piece of printer paper hiding my face below the eyes. And whenever I see that photo now, I almost comically think to myself I like that haircut but I can’t shake the memory of how terrified, lonely and vulnerable I was. I spent hours in that room alone trying to take a photo that would be an adequate reflection of me and the best I could do was a pair of scared eyes peaking above a temporary shield that hid the disfigurement of my body and the embarrassing consequences. I took and took and took those photos but that is the only one I kept.

When I was fourteen, I got a really bad haircut that I referred to as the apocalypse. Two days after the apocalypse, I actually sat at our dining room table and cried because I thought I looked stupid. This drama was met with the unfiltered disgust of my father and a pointed argument on vanity and self respect. And while I still contend that was a bad haircut, I feel fortunate for the discussion (lecture) because I strongly believe that much of maturing involves appropriately identifying and addressing the things in life you can control and the things you cannot control.

Likewise, in a perfect world, maturity is taking pride in accomplishments born of a drive or a focus or a talent and not a reflection… But we don’t live in a perfect world and I knew this because while I kept discussions of my appearance to a minimum, I no longer received any lectures on vanity or drama. Friends were sympathetic. Strangers seemed uncomfortable. And my dad had only to say, “We’ll get through this.” That isn’t to say that during that time I felt as if my accomplishments were dismissed for my deformity or that there was nothing I took pride in- but, it was a very real and very serious distraction. I believe strangers weren’t as kind to me, but even if that is just a fabrication in my mind: I wasn’t as kind to me.

As much as my appearance upset me, I also felt guilt and shame over my liver- which to this day has been diagnosed as idiopathic. That means, they don’t know what went wrong; they just know that it did. Every time I saw the distortion in the mirror, I felt embarrassed that I wasn’t stronger/healthier/better. It seemed like I wore an unfortunate mask of myself that was the price of my health and the only other people that could begin to understand how I felt were the few I could find on message boards also complaining about the tremendous side effects of prednisone on one’s appearance.

In the Spring, the doses were lowered and by May I was completely taken off the drug. Almost immediately, my cheeks adopted a certain movement to them again and if I tilted my head upward, I almost looked like I had a chin. By June, I was basically myself again and the only hard evidence I had from that time is the photo.

Whenever my dad says to me that I should consider that time in my life a character building experience, I remind him that I never needed to look that way to know that I didn’t want to look that way. That said, I think what I took most from this experience is that “vanity” is not a trivial thing to dismiss; looking well is every bit as serious as feeling well.

*****

steriod side effects,prednisone side effects, liver failure, liver failure treatment, liver disease, appearance and illness