My dad had always been defined by his strength and agility.

As a young man working his family’s tobacco farm in eastern North Carolina, as an all-star on his high school’s athletic teams, as a football player at Wake Forest University, as a soldier in the Army and N.C. National Guard: Hughie Lewis was a mountain of a man, with massive thighs and powerful muscles, and he could lift, move, control matter in a way, it seemed to us, no one else could. As his daughters, my sister and I fancied him something of a superhero.

Not even middle age slowed him down. He continued to move mountains—well, furniture, anyway, into and out of college dormitories and apartments—and take control of every situation he encountered. His strength was matched only by his love for his family. Even after he and my mother divorced when I was a young adult, he remained a powerful influence at the center of our family. We knew we could depend on him and had absolute confidence in his steadfastness and competence.

As he entered his sixties, however, we noticed changes that signaled something was wrong. He slurred his speech at times. He struggled to clear his throat, as if he were choking on mucus. He complained of feeling “drunk”—dizzy, nauseated—all the time. He had several low-speed car accidents that he was at a loss to explain. And he seemed withdrawn and disinterested in things going on around him.

As is often the case with a set of vague symptoms, it took a long process of elimination to determine the problem. And when the diagnosis came, we didn’t feel much relief at having a name for the disorder that was robbing him of his balance, vision, and muscle control: my dad had PSP, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, a rare and basically untreatable degenerative neurological disease that most doctors at that time knew very little about.

It’s a lot like Parkinson’s, I would tell people with a grim smile, only rarer and less treatable. While some strategies, such as physical therapy and modified eyeglasses, might help PSP patients manage some of the physical challenges the disease brought on, there is no medication or surgery to reverse, slow, or even treat the symptoms. And while we tried to comfort ourselves that PSP itself isn’t terminal, the truth was, and still is, that its effects are linked to common causes of death among its more infirm patients. Loss of balance and mobility increase the likelihood of falls, which often lead to life-threatening injuries or physical decline. Problems chewing and swallowing food create an increased danger of choking or aspiration, which can lead to pneumonia. Aspiration remains the main cause of death for PSP patients.

In 2000, the year of my father’s diagnosis, most Americans had only Dudley Moore, the diminutive British actor who starred in Arthur and Ten, to put a face on the disease. We followed his case anxiously. We read that he had had to stop playing the piano, which had always brought him so much joy, because he no longer had the muscle control needed to guide his fingers through the complex notes of the music. In interviews he appeared stony-faced, slurring his words much as he did when he portrayed the drunken misfit Arthur years before. His last public appearance, in 2001, was made from a wheelchair, and he did not speak. Those images were terrifying to see. (Moore died of complications from pneumonia in 2002.)

Strangely enough, for a condition so rare (affecting only 5 or 6 out of every 100,000 people), we quickly learned we had a more personal connection to the disease. My husband’s maternal aunt, misdiagnosed with other conditions for years, had finally been diagnosed with PSP in the late 1990s. Her disease was much more advanced than my father’s, and we were horrified by the news as she began to decline. When they were no longer able to care for her at home, her husband and children reluctantly moved her into a nursing home. When she could no longer swallow food without choking, her doctors inserted a feeding tube to provide her with nourishment. She lost the ability to speak. She lost the ability to pull her facial muscles into a smile, even to greet her beloved grandchildren. She was trapped in a body that was quickly shutting her off from the rest of the world. When she passed away in April of 2001, she weighed only 85 pounds.

My sister and I began a series of agonizing conversations about how we would handle our father’s care when he reached the point where he could no longer safely live by himself. We never got past the “when”—at what point something would have to be done—to discuss the “where” and “how.” The choices were too painful. My father, a fiercely proud and independent man, had always taken care of things for himself and others. His early adult years as a drill sergeant, athletic coach and high school teacher had made him a take-charge kind of man, and he chafed impatiently at the interference of others. (His favorite response to what he perceived as an impertinent inquiry from his children: “What’s it to you, you writing a book- Well, you can leave that chapter out!”) We knew he would be mortified at the thought of us, his daughters, fussing over him and assisting him with his personal care; but neither would he want to be in a nursing home, dependent on strangers—no matter how kind—for help in every aspect of his daily life. Would he consent to such curtailment of his privacy and independence- Would we have to go against his wishes for his own safety and well-being- The prospect of depriving him of his right to run his own life was almost as hard to face as the diagnosis.

And yet, for such a strong-willed, stubborn man, he had already, of his own volition, made some significant changes to his lifestyle in response to the disease. Because his vision was impaired and his reflexes slowed, he stopped driving, allowing us to take him to appointments instead. He stopped cooking and let us bring him food several times a week, because we had worried he might get burned or start a fire if he lost his footing in the kitchen. Even though he hated the appearance of disability, he began to use a walker for stability and eventually had strong metal grab-bars installed in his bathroom and shower to prevent falls. I know it couldn’t have been easy for him to do these things. But the peace of mind he gave us by making these changes—changes that, in truth, made him more dependent on us—was his most loving gift to us at a time when he was quietly grieving the loss of his old life.

The most difficult aspect of his condition, for us, was how PSP made him seem to withdraw from friends and family. Many patients with PSP are initially treated for depression, because the outward manifestations of the disease seem psychological at first: lack of interest in favorite activities, disengagement from conversations going on around them, refusal to participate in family gatherings. My father had always been gregarious, a jokester, friendly and laughing, the life of every party. A salesman throughout much of his working life, he had never met a stranger. To have our smiling, very social father suddenly replaced by a silent, slack-faced, detached stranger was deeply distressing. The changes in his speech and affect were also off-putting to those who knew him well. In fact, after his death, some of our relatives—who adored him to the point of hero-worship—admitted to me that, before learning Dad had PSP, they had wondered if he had had a nervous breakdown or had started drinking heavily. That is how dramatic the changes in his appearance and behavior were, even prior to his diagnosis. I was deeply offended at this revelation—first, that they were willing to assume such behavior was possible for a man who rarely drank and who had always faced challenges with determination and optimism, but even more that they had never come to us, his adult children, with their concerns about him.

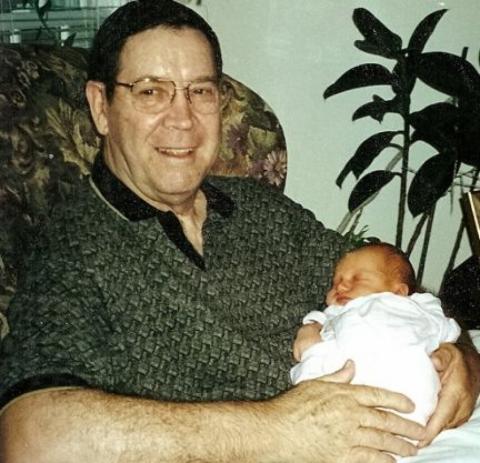

Even knowing about his condition, however, we were stunned by its effects on his interactions with us. It hit home for me when my first child was born in mid 2000. While I knew Dad was thrilled to become a grandfather at age 64, he showed little emotion when he held his granddaughter for the first time. Later, when we would visit him, he’d just stare at the television (which, really, he couldn’t see that well) rather than interact with her as she wriggled and squirmed on her blanket on the floor. It broke my heart. For a man who was all about his family, my dad’s apparent lack of interest in his own granddaughter didn’t make any sense. Then, as she became more active, the day came when he flatly refused to hold her. I was crushed, bewildered, and more than a little angry. Where was his grandfatherly devotion- Why didn’t my daughter have the same pull on him that countless nieces and nephews, even great-nieces and –nephews, had exerted- Why was he shutting her out- I shared my distress with my sister, who pressed Dad for an explanation. He quickly called me to apologize, explaining with obvious difficulty the painful truth: he was afraid to hold her. He was worried that, unsteady as he was and unpredictable as she was, he might drop her. The irony was numbing. My father had caught hundreds of football passes, handled dangerous military weaponry, built decks and desks and doll furniture for his daughters—and now he could not even hold his infant granddaughter with confidence. I was quite wrong to assume he was indifferent, that he didn’t care about having a granddaughter or about missing out on precious “grandpa” moments. His flat affect was muscular, not emotional: the disease was cloaking his emotions in an air of apathy. But inside, I finally realized, he was smiling at and loving our beautiful baby.

No doubt he was also railing against the stealthy but steady decline this terrible disease was bringing on. As if by instinct, he fell back on old friends: exercise and dogged determination. At his neurologist’s recommendation, he pursued physical and occupational therapy and quickly became the star patient of the clinic he attended. While the therapists worked to help him maintain equilibrium and mobility, he impressed them with his knowledge—from teaching anatomy years before—of the names of various muscles and bones. (“Oh, Mr. Lewis,” they would gush, squeezing his shoulders affectionately, “how did you know that-” We could detect a twinkle of his old charm in those moments.) More importantly, he never shirked from the exercises they asked him to do, and often at home he would push his walker down to his apartment complex’s exercise room and amble along on the treadmill, doing his best to maintain muscle tone and balance. Everyone was impressed with his strength of body but even more by his strength of character. He was making accommodations to PSP but he wasn’t giving up.

In the end, what my sister and I had worried about most didn’t happen. We did not have to tour the assisted living and nursing homes we had requested brochures from, and we never had to pressure our father to give up his remaining independence. Dad died in his sleep, peacefully, it seemed to us, on September 5, 2001. He was still living on his own, walking, eating, speaking. Though greatly altered by the disease, he was still years away from the extreme infirmity PSP brings on. We were not expecting him to die. His passing was a terrible shock, but quickly the realization of what he—what we all—had been spared sank in. He never had to leave his home behind, never had to use a feeding tube, never descended into silence and immobility. He did not have to endure that slow and agonizing decline, and we did not have to witness it. Though we were devastated by a loss we were completely unprepared for, we realized it was, in a way, a blessing. He died while he still resembled the man he had always been, and we could always remember him that way.