My first thought as I stepped through the glass doors was: “God, why is the reception desk behind bullet proof glass?” then, looking around at the rows of plastic chairs I thought, “I wonder how often they sterilize those.”

I moved forward reaching absently for the hand sanitizer hanging off the strap of my purse. After cleaning my hands I crossed my arms and approached the glass wall that was the reception area. The woman behind the thick glass asked my name. I gave it, and she told me to sit, they’d call me when it was my turn. I nodded. Before I could turn away she pushed a clipboard through an opening and said, “Go ahead and fill this out while you wait.”

I did, but I used my own pen. I always have my own pen.

It felt like I was waiting for hours. I watched the people around me to see if anyone seemed unwell. And more than once I twitched with the urge to just get up and leave. This was stupid. No one could fix me. I’ve been this way for over thirty years. Most likely they were just going to tell me I needed drugs.

When the woman called me back, I stood slowly, looking back at the doors that led out of the building and to freedom. It was my last chance to get out of there. But I went, because making a scene was almost as bad as using a public bathroom.

I was led into a room, just a regular office with a desk and bookshelves against the back wall. A woman, not much older than me, sat facing her computer. She told me to sit, and so I did.

“Tell me why you’re here,” she smiled at me.

“I have emetophobia.” I said, and that was most of it, but not all of it.

She looked a bit puzzled, “emetophobia?”

“Phobia of vomit,” I told her. My first twinge of doubt crept in at that moment. She was supposed to know about phobias, wasn’t she? I mean, it was a mental health clinic.

“Oh, so…” she pulled open a drawer and hefted out a book as thick as a shoebox. She flipped it open, paged through and looked up saying, “We’ll just call that ‘specific phobia’.” She marked this diagnosis on what I assumed was my file. “Can you tell me about this phobia?”

I explained that I’d had it for as long as I could remember. I told her there was not a traumatic moment that gave birth to this stupid fear. I told her that my main concern was that it was making it hard for me to work, to leave my house, and be social. And worst of all, I was scared of passing it on to my son.

She said, “I have to ask you a few questions, they’re just screening questions to see where you are on a few scales.”

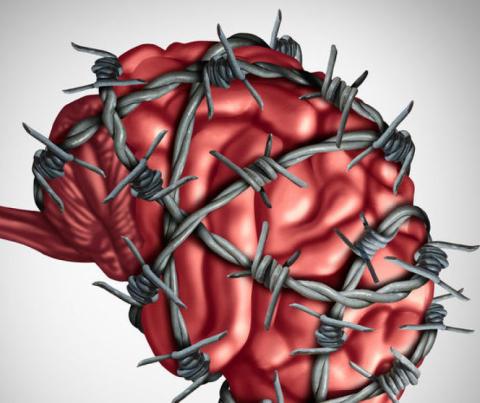

I spent an hour with this woman who probed into my mind as much as she could. Through her questions I realized there was more to my problems than just an irrational fear. She made me realize that I also felt hopeless, helpless and worthless. All of which sounded like the same thing, but really weren’t. I wanted help. I needed help!

Many things made me hesitant about getting help, though. At that moment my biggest hesitation was money. After what I’d shared with her, and how understanding she’d been, I felt it was time to breach the subject of money, or, the lack thereof. So, looking at my hands I said, “I can’t really work because I’m afraid of getting sick.”

She didn’t reply.

I went on, “I’m afraid I won’t be able to pay for treatment.”

“Well, the truth is,” she said, “we won’t turn you away if you can’t pay. We’ll bill you, we will ask that you try to make payments, but our main concern is that you get better.” Then she asked, “How does not having a job affect your life?”

I explained that it put a strain on my marriage, and made me feel like a burden on everyone around me. She gave me a sympathetic answer, something along the lines of, “that must be hard.” I told her it was. I also admitted that I’d thought of trying to apply for disability because of it.

She nodded, said it might not be a bad idea, then, standing she told me I would see a nurse next.

My heart sank. A nurse? Nurses deal with sick people daily! They hold buckets under the mouths of vomiting people! They wear scrubs stained with bodily fluids. And due to my phobia I knew that simple washing wasn’t effective in killing germs in fabric, it took bleach. I wondered if nurses washed their scrubs in bleach. I wondered if they took them home to wash them. Probably not. I wondered how often they infected their whole family with something nasty they brought home from work.

I did not want to see a nurse.

I felt a bit dizzy, but I followed the woman out of her office and into another one. My heart was beating faster, my hands went again to my sanitizer and I filled the air with a cloying artificial fruit smell of cherries and berries. She ushered me into a room with no desk, laminate flooring, and a blood pressure machine in one corner and cabinets that looked very much like those in a doctor’s office. Three chairs were the only furniture in the room. I just stood there, arms crossed, hands tucked into my armpits.

“The nurse will be here in just a minute,” the woman said, and left me. Again I used my sanitizer. The door swung open as I clicked the lid to the little hanging bottle closed and a man stepped in. He must be the nurse. His scrubs were dark blue, and I thought, “Those don’t look like they’ve ever been bleached.”

He stuck out his hand with a grin and said, “Hi, I’m Jorge, nice to meet you.” He had a thick Hispanic accent, and eyes that were such a dark brown they almost looked black.

I shook his hand. I didn’t want to, but I also didn’t want to refuse. I was trying to act like a normal human. “Kelli.” I smiled. Everything in me wanted to reach for my hand sanitizer, but I didn’t.

He said he was going to take my blood pressure and I nodded. He asked why I was there. I told him. I also told him that I was scared of germs, and since he was a nurse that he made me nervous.

“Oh well, I’m a clean guy,” he said laughing. He extended his hands to his sides and said, “you know germs are everywhere, anyway, so there’s no way to avoid them.”

I nodded. My doubt bubble grew.

He motioned for my arm and I held it out, as he took my blood pressure he asked me questions and told me what was expected of me. “I’ll need to know if you’re taking any drugs.” He smiled, “legal or not. They’ll probably prescribe you something for anxiety, so be honest so we don’t have interactions.”

I laughed: one humorless exhalation. “I don’t even drink. I’m scared of getting sick. I’m hoping we can figure out a way to make me better without pills.”

He shook his head still grinning, “No, they’ll give you a prescription.” He went on to explain how the drugs were thought to work and how it would benefit me to just do what the doctor told me to. Then he asked, “So, you’re not on any drugs?”

I told him, “I sometimes take l-theanine.” It was an herbal supplement thought to help with anxiety and it did seem to work.

His expression, the reassuring grin he’d been wearing the whole time, faltered. His eyes narrowed just a bit and he gave me a look that one might give a kid who just said they have a friend that’s a fairy with pink skin. “That stuff doesn’t work.” He told me flatly.

Doubt clawed at my stomach. He had just told me that they weren’t sure how anti-anxiety meds worked. Why then, did he find it so hard to believe that an herbal supplement might help? But I laughed and agreed with him. “Yeah, I’m sure it was just in my head, but at least it helped me a little when I needed it.”

He continued to give me a patronizing look. “So, I’m going to give you the address to the clinic to have your blood drawn.”

I tried not to sound panicked when I asked, “clinic? Do I have to go to a clinic?” In a small voice I added, “That’s where sick people go.”

He scoffed. He actually looked at me and shook his head. I wondered how this man could work with mentally ill people and not have any sympathy. Was it just me? Was it something I said? Was it just because he thought I was stupid? That my fear was stupid? The air filled with cherry berry smell, I hadn’t even realized I squeezed into my palm.

He said, “You have to have your blood tested so they can find the right prescription for you.”

Again with the pills. I just nodded. I was beginning to realize that this nurse didn’t really want to hear my fears; he didn’t care about my problems. I’d play along.

He gave me the address on a piece of paper I imagined to be crawling with germs and I shoved it in my back pocket. He looked down at his clipboard and said, “disability?” He didn’t even try to hide the distain now. “You won’t be able to get on disability for this. You can try,” he actually stuck his nose in the air when he said this, “but you won’t get it.”

I shrugged. “I just thought it might help me pay for treatment.”

“For the drugs you don’t want?” he laughed. It was almost a convincing laugh. Like maybe it was just a friendly joke.

I smiled. It was all I could manage.

From that point on I just answered his questions. I didn’t add anything. I didn’t ask any questions of my own. I knew I’d never be back. I knew that I could not go to a clinic and be in a waiting room where sick people would sit beside me. Where they sat in hard to clean cloth chairs I’d have to sit in, where they clutched doorknobs that I would have to touch.

I get it, I’m frustrating. I refuse the sort of help most doctors want to offer. I am timid and soft spoken. I want help, but I’m scared of it too.

I just wish he would have been kinder. More tolerant. I’ve since decided that perhaps he thought I was faking it, that the first thing he saw when he looked at my paperwork was “disability” and decided I was only trying to get money for nothing. I don’t know.

What I do know is, I haven’t sought help since. Why would I seek out what I felt was a total humiliation again? I put myself out there. I took a step in the right direction and then I let someone with a bad attitude, or perhaps a bad opinion of me, turn me away.

I’d like to try again someday. For my son, if not for me. But I just can’t get bear the thought of living through this horrible experience again. What if it was me? What if I am annoyingly broken, or just too sensitive?

What if I’m right and there’s just no fixing something that’s been damaged for over thirty years?