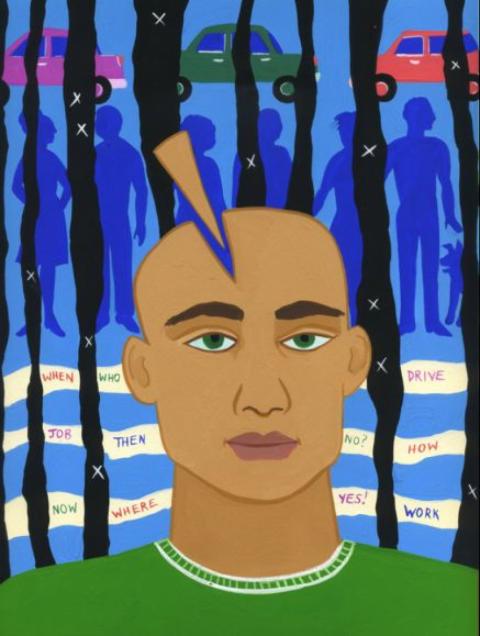

They start as brief periods of disorientation. Family members don’t understand strange statements which won’t be remembered by the victim. Every day life becomes a game of Russian Roulette as the strange periods come at an unknown moment which can be deadly from a position behind the wheel of a moving vehicle. Finally a diagnosis of a rare type of seizures at least brings some understanding of a difficult dilemma.

For whatever reason my battle with the unusual complex partial seizures started in my mid-thirties. The first indications came after a Sunday afternoon drive. My wife thought I was playing some sort of game when I said I couldn’t remember it.

The rest, as they say, is history. That history included events that nearly led to emergency choking procedures in local restaurants as locals tried to understand my actions. It included public events that were stopped in order to allow for my treatment by a rescue squad. There were no gyrating movements or wild moments of physical dangers to the body. Instead brief, often only seconds-long periods, of confusion, strange talk and memory loss marked each seizure. I faced zombie-like behavior and then no memory.

People who are part of my everyday life told me of hundreds of such events. There is no way of determining how many occurred when I was alone. Often a brief feeling of what those with epilepsy call an “aura” gave brief warning but not enough to take preventative action.

The nightmare stopped only after family members tried to describe the events to physicians. It finally screeched to a halt after three hospitalizations, a false diagnosis and an expert at the local state hospital who final came up with the right result.

After years of dealing with this epilepsy and its affects, including several automobile accidents and the loss of driving privileges, I made one of the most difficult decisions of my life. I chose to allow surgeons access to my brain, which led to pain, fatigue and complete dependence on family members. Eventually the ordeal was worth the reward as the process led to a new life for me as well as family members.

The very thought of brain surgery sends a chill through the spine of patients, family members, and even doctors, who choose to try other options before resorting to surgery. Just the thought of potential dangers sends many in other direction of treatment. I was one of those chose the route of a partial lobectomy over a life with epilepsy. I was one who decided to play the numbers and strive for an answer.

The thought of a surgical injury to the organ that controls the rest of the body is a difficult one to digest. Brain damage can affect the function of any body organ and the loss of such necessities as sight or hearing. Doctors make those possibilities clear when presenting the options and they are a critical part of the final decision.

My first reactions when presented with the proposition of surgery were ones of obstinate refusals. Any other options seemed more appealing. I vividly remember the day of reciting that “no one will be cutting into my head.”

First doctors chose other alternatives. The most common treatment of epilepsy is a cocktail of medications, but an assortment of drugs could not stop what became a life of apprehension dreading the next seizure. A total of five drugs at different times decreased the number of seizures but a written record continued to be marked by an “x” on a calendar or in a small notebook marking a day of a seizure.

As I repeatedly reached a seizure free week, aspirations of hope would be dropped to dreaded feelings of humility by another seizure, meaning the road to my license was longer once again.

An innovative approach involving treatment of sleep disorders was exciting at first but did not offer significant help.

The drugs and other treatment attempts could not convince the state that I was not a hazard to others and myself as I took to the road. They could not relieve the burden the disease had caused family members, some of whom had altered career paths to make them more available to meet my transportation needs associated with work requirements. They could not relieve my burden of trying to cover the news of a county through a job at a local newspaper while depending on others to move me to story locations.

These factors and the simple diversion of the fight against the disease led me to do what my wife and I said we never would.

More than a dozen trips to the doctor and his patient persistence led me to agree with the medical opinion that removal of brain matter held hope for improvement. The result of that decision was an experience that will be remembered by every person who helped me get through it. It became more than any of us expected.

An issue with one testing measure created the need to insert probes on both sides of the brain to determine the precise location of the damaged matter. As I had so many times before during a two year evaluation process I faced plastic probes placed all over my head, recording brain activity and data that would make the tasks of doctors easier.

The first procedure was followed by five days of waiting and observation before the actual process of removal began. Recovery was memorable to all involved. Doctors joked with my wife about my drug inspired singing and my jovial behavior throughout the process of coming to my normal level of consciousness. I vaguely remember the staggered speech and feeling of euphoria that came over me. The warm feeling of familiar faces still lingers in the back of the brain that went through so many traumas that day.

As faint as the memories of the actual surgery are for me family members talk of days they won’t forget. They talk of hours of small talk and shallow jokes, and then distress as the day wore on. They mention relief and joy at the sight of a tired physician making his way out of the operating room.

I don’t remember the labors of those talented surgeons but the long scar slicing down my head in the form of a question mark shows the proportion of their work. The same marathon endured by my family was a mere moment to me. One minute I was being wheeled into the operating room saying goodbye to family and the next it was over. Eventually I woke up which is where the memories began to flood in. That is where I questioned my decision, wondered why I would do anything that caused that much pain. I wasn’t thinking of a seizure free life, but instead just a pain free moment.

My first memories of waking up from surgery are with one eye swollen shut with a new fear that I was blind. I remember the steady throb of a jaw muscle recovering from a severing blow from a surgeon's knife. Every beat of my heart brought a hammer like blow to my temple, and another bead of sweat as my body tried to deal with the stifling heat of the recovery room.

A high dose of narcotics relieved these symptoms but also erased much of the next ten days from my memory. I do remember the satisfaction of seeing the building where my personal miracle had occurred in the rear view mirror. I remember feeling more love from family than at any time before or even since. I also remember having no idea of what the days ahead held.

Even though the drugs have taken memories of parts of the next stage of the recovery from me I do remember the shock of how much the event had affected me. In those early weeks one lap around the living room was enough to send me back to my bed. Even the task of breathing became painful because of the effects of many hours lying unconscious under surgery lights. Eating was a chore as a recovering jaw, cut purposefully during surgery, had only limited usability. Each meal brought the possibility of nausea that plagued me during hospitalization. Many days were spent in dark rooms, with blinds shut and even the blue glow of the television bringing with it pain in areas around the surgery.

Venturing from bed was an eventful part of each day; even those few steps were dangerous as a complete depletion of balance made walking dangerous. A metal walker became my best friend on the few occasions I ventured out of the home. Movement to a cane was one of the significant steps on the ladder to recovery.

Family members were like gold as they helped me get through life’s simplest tasks. Trips to the shower or the couch in the next room were major challenges and the faces of family in the room to help were always pleasures.

The visit of the physical therapist was not as welcomed. That meant grueling two-hour segments of rebuilding strength. She brought with her a regiment of physical exercises that eventually put us on the trampoline for balance exercises and on neighborhood streets for strength building walks.

The days of recovery were not all bad. I achieved a new and real appreciation of life’s simple pleasures. There were moments when the appearance of children at the door brought a smile. There was the day when my beloved four-legged friend was allowed a visit, bringing the familiar feel of her warm tongue as she tried to understand the situation.

There were hours spent with family members that would have otherwise faded into the routine of my life.

Two years after the surgery I look back on the experience with a sense of pride, my scar at times feeling as a battle scar, of a battle I won. With only one seizure since that time there is little doubt about the success of the treatment. The only nagging reminder of my ordeal is the still regular routine of medications as a preventative measure.

The only lasting side affect are slight headaches in the area where the surgery was performed, most often coinciding with changes in the weather. There are still precautionary measures such a pre-haircut warnings to overzealous barbers who come precariously close to my battle scar with their instruments.

There are occasional days of self-pity when I see the large reminder of my ordeal and a lingering fear of what affects a once forbidden alcoholic beverage could bring me in my new life.

All of these simple inconveniences have been easily implemented to the new life, given back by the most difficult gamble I have even taken that provided the biggest reward.

I am not sure what I expected from surgery but what I got is my normal life, which is impossible to measure. I now do not fear getting behind the wheel as I did before surgery. There is no guilt associated with return trips to the urns carrying my beloved sweet tea, wondering if caffeine, often a stimulus to problems, in that that last glass would cause problems later in the day. I don’t worry about the amount of sleep, fearing a shortness of sleep time might cause the dread of another period of unconsciousness.

There is no doubt deciding to have surgery was one of the most difficult of my life. There is no doubt the recovery from surgery was the most difficult physical challenge of my life. I would still not hesitate to recommend surgery to anyone in the same seat where I sat. Anyone considering surgery should get ready for a difficult ordeal and prepare for a normal life. As doctors repeatedly told me there is a chance of failure and many don’t have the result I did but I think even the small chance of success is worth the risk.

Brain surgery was the most difficult decision to make but now my wish is I would have been able to do it sooner.