“You could lose your sight.”

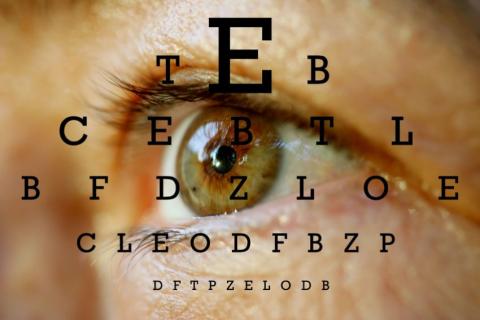

The words stabbed me in the heart as I stared up at the ophthalmologist, certain I’d heard her wrong. For as long as I can remember, I’ve had severe dry eyes with photosensitivity. I never went outside without wearing sunglasses even in cloudy weather, and I had a bottle or two of eye drops in every room of my house and my car. I just assumed it was something I’d have to live with.

Lately, though, my eyes had gotten worse, the pain going from moderate to excruciating. Many times, I kept them closed because that soothed them somewhat. But I couldn’t continue that way because the pain was starting to affect my job. So, I’d sought help from another ophthalmologist, hoping there was a miracle cure.

“What do you mean? I just have dry eyes. That can’t cause me to go blind.” Desperate for her to change her opinion, I pelted her with question after question. “Are you sure? What can be done? What are my options?”

The doctor, in a patient, calm tone of voice, explained that I had nodules on my corneas as well as scar tissue. A few other large words came up, but I didn’t bother to ask her what they meant. There was only so much information I could absorb without falling completely apart in the exam room.

Nearly hysterical, I shook all the way out to my car and sat behind the wheel for a long time before putting the key in the ignition. The ophthalmologist had given me two prescriptions and a referral to a retina specialist. Though she’d sounded optimistic, I’d seen the look on her face. She’d been concerned, and I had enough health issues to know it’s never a good thing when a doctor is concerned.

Had I let this go too long? Had my dry eyes evolved into something much worse? Was losing my vision really a possibility, or was this the doctor’s way of scaring me into following up? If that was the case, it worked. My next phone call was to the retina specialist about four hours away from me.

My eyes burning from an excessive amount of tears, I drove home in a quiet fog. The logical side of my brain insisted on forming a battle plan. With the next appointment scheduled, I now had to arrange lodging. No, wait. I had a friend who lived in the area. I needed to pack. No, not yet. My appointment wasn’t until the following week. That was the earliest one I could get.

Time crawled by, minutes seeming like days. I spent my time researching the blind, watching hours upon hours of videos of individuals who were leading happy and fulfilled lives. I bookmarked page after page of information I thought I’d need in just a matter of time.

By the time I arrived for my appointment, I’d convinced myself I was ready for whatever this doctor would tell me. Except I wasn’t. He didn’t greet me with gloom and doom or dire predictions. Instead, he laid out the options and explained they might not work, but they had a chance.

My eyes were severely damaged, but there was no guarantee I would lose my vision. Though the possibility was high, I still had hope with a new regimen that involved steroids, surgery to remove scar tissue, and hundreds of miles driven back and forth between my home and the retina specialist.

Just as the load had lightened, and I started to feel like myself again, I learned that the eye surgery had been for nothing. The scar tissue had grown back, even worse this time. The doctor wouldn’t perform another surgery. The best I could hope for was keeping the scar tissue at bay with more steroids.

For months after learning that piece of news, I lived in fear. I was terrified each morning when I opened my eyes that I wouldn’t be able to see the world around me. What I didn’t realize was how I was limiting my life before I’d lost anything. Though I kept living as a sighted person, I could only focus on what I was sure was going to happen any day.

Then one day, the vision in one eye went gray. I saw nothing but shadows, and I was sure this was the beginning of the end. But there was no medical reason for the loss of sight, and it returned within a day. Perhaps my mind had grown so convinced of the eventuality that it manifested the vision loss. I only know that when my sight in that eye returned, I rejoiced like a child with an ice cream cone. It was a wake-up call for me. I couldn’t plan my life around what might or might not happen.

I still have pain and scar tissue, but, so far, I still have my sight. There may come a time when there is nothing more the doctor can do, and I’ll lose it, but I’m refusing to dwell on that now. I might have only a year or two left with vision, but then again, I could have ten years. All I know is the sight I have now is worth living for.

I still get nervous occasionally about my future, but I refuse to live in panic. I’ve watched so many blind people living complete, fulfilled lives. Some of them were born without sight, but others lost theirs in later years. And they’ve discovered that life can be just as good. That’s what I choose to think about. Should I lose my vision in the years to come, even with the overwhelming sense of loss, I know my life will still be worth living.